At midnight on June 25, 1975, India—the world’s largest democracy—froze. Prime Minister Indira Gandhi had declared a nationwide Emergency. Civil liberties were suspended, opposition leaders jailed, the press gagged, and the Constitution bent to concentrate power in the executive. For the next 21 months, India remained a democracy in name alone.

The trigger? A damning verdict from the Allahabad High Court found Indira Gandhi guilty of electoral malpractice and invalidated her 1971 election win. Facing possible disqualification and rising street protests led by socialist stalwart Jayaprakash Narayan, Gandhi responded by invoking Article 352 of the Constitution, citing “internal disturbance” and threats to national stability.

Historian Srinath Raghavan, in his book on Indira Gandhi, notes that while the Constitution permitted wide powers during an Emergency, what followed was “extraordinary and unprecedented strengthening of executive power... untrammelled by judicial scrutiny.”

More than 1,10,000 people were arrested, including senior opposition figures like Morarji Desai, Jyoti Basu, and LK Advani. Political groups across the ideological spectrum were banned. Prisons overflowed. Torture was routine.

The judiciary, stripped of independence, offered little resistance. In Uttar Pradesh, which detained the highest number of people, not a single preventive detention order was overturned. “No citizen could move the courts for enforcement of their fundamental rights,” Raghavan writes.

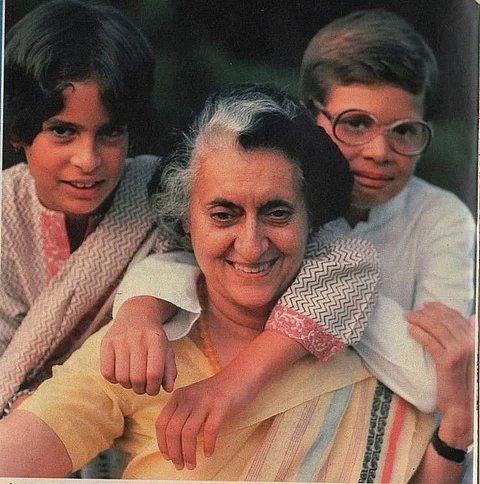

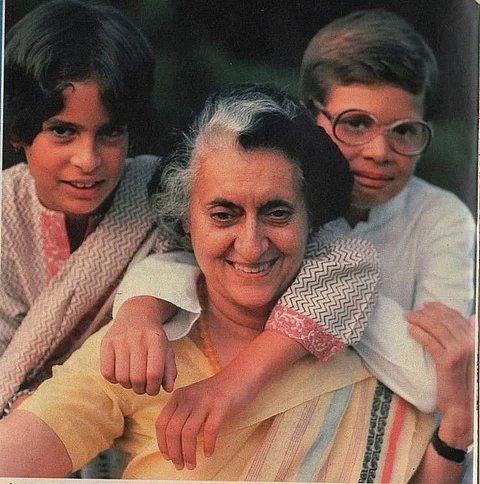

The most controversial policy of the Emergency was a brutal family planning campaign. Around 11 million Indians were sterilised—many by coercion. Though officially a state programme, it was widely seen as the handiwork of Sanjay Gandhi, Indira’s unelected and increasingly powerful son.

In a Delhi neighbourhood on the Uttar Pradesh border, dubbed “Castration Colony,” women reportedly said they’d been made bewas—widows—not by death, but by forced sterilisation. Police in Uttar Pradesh recorded more than 240 violent incidents tied to the campaign. Cash incentives for sterilisation often equalled a month’s wage. Contract labourers were reportedly told, “No advances, no jobs, unless you get vasectomies.”

Civil rights activist John Dayal and journalist Ajoy Bose, in their book on Delhi during the Emergency, described the intense pressure on officials to meet sterilisation quotas, leading to widespread abuse.

Parallel to this, a massive urban “clean-up” drive displaced hundreds of thousands. Nearly 1,20,000 slums were demolished in Delhi alone, displacing some 7,00,000 people, many relocated to far-flung resettlement colonies. In Turkman Gate—a Muslim-majority area—police opened fire on protesters resisting demolition, killing at least six.

The press, meanwhile, was silenced overnight. Power to newspaper presses in Delhi was cut on the eve of the Emergency. By morning, censorship was law. The Indian Express left its editorial column blank. The Statesman followed suit. Even The National Herald, founded by Nehru, quietly dropped its masthead slogan: “Freedom is in peril, defend it with all your might.” Shankar’s Weekly, famed for political cartoons, shut down entirely.

Journalist Coomi Kapoor, in her memoir of the Emergency, details blanket bans on media coverage—from slum demolitions and prison conditions to any criticism of the family planning drive. Even seemingly trivial stories were censored, including reports about a bandit or a Bollywood actress caught shoplifting in London.

Foreign correspondents like the BBC’s Mark Tully and journalists from The Times, Newsweek, and The Daily Telegraph were expelled for refusing to sign “censorship agreements.” Years later, Gandhi reportedly told the BBC chief she hadn’t lost public support—“only the people were misled by rumours, many of which were spread by the BBC.”

A few judges pushed back—high courts in Bombay and Gujarat ruled that censorship couldn’t be used to “brainwash the public”—but such resistance was quickly neutralised.

Meanwhile, Sanjay Gandhi launched a personal five-point programme—family planning, tree planting, anti-dowry advocacy, adult literacy, and caste abolition—which was enforced through the Congress party’s youth wing. Congress president DK Barooah ordered party units to implement Sanjay’s five points alongside the government's 20-Point Programme, effectively merging personal diktats with state policy.

Anthropologist Emma Tarlo described how the poor were reduced to “forced choices” under the Emergency. It was also a turning point in industrial relations: around 2,000 trade union leaders were jailed, strikes banned, and labour protections gutted. “The last vestiges of working-class politics were imperiously wiped out,” wrote Christophe Jaffrelot and Pratinav Anil in their history of the period.

The result? Strikes dropped from 2.7 million workers in 1974 to just half a million in 1976. Mandays lost to stoppages plummeted from 33.6 million to 2.8 million. Business flourished. JRD Tata praised the regime’s “refreshingly pragmatic and result-oriented approach.”

Despite its authoritarianism, some viewed the Emergency as a period of order. Journalist Inder Malhotra observed that in its early months, “the Emergency restored to India a kind of calm it had not known for years.” Trains ran on time, production rose, crime fell, and inflation eased, aided by a good monsoon.

As historian Ramachandra Guha noted, “One fact is conclusive proof of the quiescence of the middle class—that hardly any officials resigned in protest.”

The harshest measures were largely concentrated in northern India, where the Congress had a tighter grip. Southern states, governed by stronger regional parties and supported by resilient civil societies, resisted or moderated New Delhi’s excesses.

The Emergency ended in March 1977 when Indira Gandhi, confident of victory, called an election—and was defeated. The new Janata government rolled back many Emergency-era laws, but the damage was done.

Historian Gyan Prakash argues that the Emergency exposed how democratic structures could be hollowed out from within—legally. “Indira’s suspension of constitutional rights appears as an abrupt disavowal of the liberal-democratic spirit that animated Nehru and other nationalist leaders,” he wrote.

Yet, he warned against the complacency of seeing it as a one-off aberration. That narrative, he wrote, fosters “a smug confidence in the present” and encourages “an impoverished conception of democracy”—one that values only rituals and procedures, not substance or accountability.

The Emergency, ultimately, was a stark warning: democracy can crumble not just through revolution or invasion, but from within, when institutions fail to check power and the people surrender liberty for the illusion of order.